The

determined message of Martin Luther King's famous speech will be as

important as ever as people from across the country travel to Washington

to protest racism.

Protesting Trayvon Martin's murder and the targeting of young Black men

Protesting Trayvon Martin's murder and the targeting of young Black men

FOUR-AND-a-half years ago, an enormous crowd packed into the Capitol

mall in Washington, D.C., to celebrate the inauguration of Barack Obama.

The first African American president took the oath of office in front

of a Capitol building built by slaves.

Among the crowd on that January day, there was a sense of bearing

witness to progress--not only because of the historical significance of

the first Black president in a country founded on slavery, but also the

seeming sea change in contemporary politics after eight long years of

George W. Bush and the Republicans in power.

This weekend, another crowd--smaller, but likewise dominated by

African Americans--will gather on another part of the mall. They will be

commemorating a different historical moment: the 50th anniversary of

the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, where Martin Luther

King Jr. gave his "I Have a Dream" speech.

But they will also be protesting--expressing their anger at the

continuing grip of racism in so many forms, even as an African American

sits in the Oval Office.

By virtually every measure, the conditions and quality of life for

the majority of African Americas have declined during the Obama years.

More than other parts of the population, Black America has borne the

brunt of the economic and social crisis of the Great Recession years.

The March on Washington is an opportunity to focus a spotlight on this

reality, while the cameras of the media are rolling--and on the need to

do something about it with, as King said 50 years ago, "the fierce

urgency of now."

Not only is racism still with us--despite the claims that we are,

since Obama's election, living in a "post-racial society"--but the first

African American president has done nothing about the crisis of Black

America. On the contrary, for the last five years, Obama and his

administration have explicitly avoided being identified with "racial

issues."

This posture changed somewhat over the summer. Last month, Obama made

one of the only public statements of his presidency about racial

profiling and racism in the U.S. justice system--but only because of the

wave of outrage after the acquittal of George Zimmerman, the murderer

of Trayvon Martin. Likewise, Attorney General Eric Holder promised

changes in the Justice Department's policies on drug prosecutions and

mandatory minimum sentencing--after years of upholding the federal

injustice system.

Obama and his administration will get credit they don't deserve for

these statements and promises--among liberal leaders of mainstream civil

rights organizations and unions who will speak at the March, and also

among the crowd in general. Those committed to building the antiracist

struggle should take the opportunity this weekend to talk about the real

record--and about why liberal leaders who apologize for that record,

rather than challenge it, are making the situation worse.

Still, even if Obama and Holder are taken completely at their word,

it won't be news to anyone at the March that much, much more needs to be

done--and that the initiative for doing it is going to have to come

from outside the Washington political system, as it did after the

Zimmerman verdict.

That's a sentiment to build on--with the aim of using this national

mobilization against racism to advance local struggles around a wide

range of questions that marchers will return to on August 25.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

THE AUGUST 24 demonstration would have been an important historical

commemoration no matter what, but it took on a new dynamic after the

Zimmerman verdict.

The acquittal of a self-declared neighborhood watch captain who

stalked and killed an unarmed Black teenager dramatized how much the

issues of 50 years ago are with us today. A young Black man walking

after dark where someone decided he shouldn't be, his murderer declared

not guilty by a jury without a single African American--all that would

be very familiar to the marchers of 1963.

The issues of racial profiling and vigilante justice, carried out by

killers in uniform and out, naturally became one important hub for the

mobilization to Washington.

In New York City, participants in the struggle to win justice for the

victims of police murder like Ramarley Graham and Shantel Davis filled

up one bus by themselves and are looking for any way to get more people

to D.C. Among the thousands of others from New York will be those who

marched down Fifth Avenue last year in a silent protest against

"stop-and-frisk," the NYPD policy that a federal judge this month found

had violated the constitutional rights of hundreds of thousands of Black

and Brown New Yorkers.

There are other issues driving the turnout--as numerous as the many

faces of racism in U.S. society. In Chicago, the Chicago Teachers Union

is among the organizations behind the Chicago Labor Freedom Riders

caravan to D.C. Its participants want to emphasize how the assault

against public education and public-sector workers is bound together

with the attack on Black America.

So whether they've been to Washington protests before or are

attending their first national demonstration, many of those at the March

will be no strangers to struggle. For them, the bus rides to and from

D.C. and the rally and march itself will be a chance to build up

networks of solidarity--to make connections to people involved in the

same struggles in other cities, or their neighbors organizing around

different issues in their own hometown.

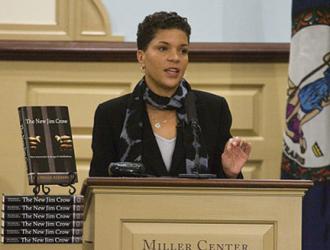

Thus, Joseph "Jazz" Hayden of the Campaign to End the New Jim Crow in

New York City is hoping the March on Washington will help activists

sink deeper grassroots far beyond the capital. As he told

SocialistWorker.org:

We saw the grassroots response to the Trayvon Martin decision, which led

to demonstrations in over 100 cities across the country. Imagine if we

were organized in 100 cities across the country. Anytime we decided we

wanted to put something on the national agenda, we could put it out

there instantly.

In addition, every person who brings their experiences to Washington

and every struggle represented at the March will add to the ideological

alternative to the conventional wisdom that has dominated mainstream

U.S. politics--that the problems of the Black community are largely, if

not entirely, the fault of the Black community itself.

That scapegoating message has been constant since the end of the

civil rights era in the mid-1960s, when openly preaching the inferiority

of African Americans fell out of favor in mainstream politics. Instead,

racism was repackaged, often through coded appeals for "law and order"

and "personal responsibility." Today, the idea that Blacks--and not the

system--are to blame for their own oppression is accepted across the

political spectrum, including, in varying degrees, by leading figures in

the Black community.

But as Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor wrote for SocialistWorker.org:

[E]very once in a while, something happens that tears the mask off,

revealing the ugly face of U.S. society. The murder of Trayvon Martin

and now the acquittal of his murderer confirms again that racism is so

tightly packed into the blood and marrow of American democracy that it

cannot live without it.

The assembled masses of the marchers in Washington will be definitive

evidence, for anyone who cares to listen, of both the depth of the

crisis of Black America and the fact that its causes lie in systemic

oppression that is woven into the fabric of U.S. society and Washington

politics.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

NO OPPONENT of racism doubts that the Republicans and their

right-wing base are committed to bigotry and discrimination. They all

but say so themselves.

Case in point: The Supreme Court decision in June, by a 5-4 majority

along ideological lines, that gutted one of the main accomplishments of

the civil rights movement: the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Gallingly, the conservative justices claimed that racist obstacles to

voting rights were a thing of the past, and therefore the act's major

protections could be done away with. That's a blatant lie--six of the

nine states that were specially scrutinized under the Voting Rights Act

passed new voting restrictions since 2010. All told, 19 states passed

more than 24 measures in 2011 and 2012 that make it harder to

vote--practically speaking, harder for

people of color to vote--and there's worse to come following the Supreme Court ruling.

The ugly logic is clear for Republicans--fewer Black and Brown voters

means fewer votes against them. Thus, the call for Congress to update

or amend the Voting Rights Act will ring out from the stage at the March

on Washington, and rightly so.

But many speakers will be hesitant to talk about issues where the

Democrats have a hand in implementing racist laws and policies. Take the

issue where Attorney General Holder recently spoke out: the "war on

drugs" laws that have been a leading cause of the incarceration boom in

the U.S.

Earlier this month, Holder told the American Bar Association that he

would urge federal prosecutors to avoid charging defendants in

nonviolent drug cases with offenses that carry mandatory minimum

sentences--one of the main contributing factors in the 800 percent

increase in the federal prison population since 1980. But there are

holes in Holder's announcement--not least that it will be up to

prosecutors whether to exercise the discretion Holder is allowing them.

Plus, Holder's new promises come after four-and-a-half years when the administration has

enforced some of the most unjust and racist policies of the decades-old drug war.

In June, for example, Holder's Justice Department argued in court for

enforcing existing sentences for prisoners under the notorious 100-to-1

rule--a sentencing guideline where mandatory minimums were triggered

for possession of a hundredth of the amount of crack cocaine (where

users are more likely to be Black) compared to powder cocaine (more

likely to be white).

In 2010, Obama signed the Fair Sentencing Act, which dropped the

disparity to 18-to-1--still a half measure that Jasmine Tyler of the

Drug Policy Alliance described as a license "to be a little racist."

But when a federal appeals court ruled that the new "fair" sentencing

should be applied retroactively for drug possession convictions,

Holder's lawyers went to court to oppose the decision--in effect, asking

that thousands of people, most of them poor and people of color, remain

behind bars under a sentencing guideline the administration itself

repudiated.

That Holder this month proposed reforms around mandatory minimums "is

a reflection of a change in public opinion and a rising tide of

activism among prisoners here in California and their families," Isaac

Ontiveros, an organizer with the prison abolition group Critical

Resistance, told the Common Dreams website. But the struggle against the

New Jim Crow can't end there, any more than civil rights activists of

the 1950s and '60s would have been satisfied with their first partial

victories against old-style Jim Crow segregation.

This weekend, people will come to Washington, D.C., from across the

U.S. to show their opposition to racism and send the message that action

is needed. The words of Martin Luther King's famous speech will be as

important as ever:

We have...come to this hallowed spot to remind America of the fierce

urgency of now. This is no time to engage in the luxury of cooling off

or to take the tranquilizing drug of gradualism...The whirlwinds of

revolt will continue to shake the foundations of our nation until the

bright day of justice emerges.

http://socialistworker.org/2013/08/22/the-fierce-urgency-of-now