By Max Kantar

http://t.co/VwDBbTd

Michelle Alexander’s recent book, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness,[1] may well be the most important analysis of the current state of human rights and racism in American society since W.E.B. Dubois wrote The Souls of Black Folk at the turn of the twentieth century.[2]

In it, Alexander, a distinguished professor at the Moritz College of Law at Ohio State University and the former Racial Justice project director for the ACLU of Northern California, argues that the mass incarceration of black and brown men in the United States amounts to a complex system of racial control with uncomfortable and uncanny parallels to Jim Crow, both in terms of its scale and the real life consequences for people of color, African Americans in particular.

In fact, under the auspices of the War on Drugs, the United States incarcerates black men at nearly six times the rate that the internationally reviled white supremacist South African regime did at the height of apartheid.[3] Today, there are more African Americans under correctional control—in prison or jail, on probation or parole—than there were enslaved in 1850, more than ten years before the Civil War began (p. 175).

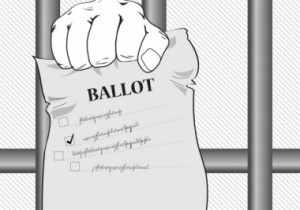

In major cities, large majorities of Black men have been branded felons for life—mostly for minor, nonviolent drug offenses—effectively locking huge sectors of the black community into a permanent second-class status where they are legally discriminated against in all the same ways that their grandparents were during Jim Crow, including access to housing, employment, and public benefits, not to mention systematic exclusion from juries, denial of the right to bear arms, and denial of the right to vote, all in accordance with the law.

Racial Caste Reborn

One of the major themes in The New Jim Crow is that racial caste in America is an institution that has persisted over the years by evolving—through conscious policies and political campaigns—in order to adapt to serious challenges to its legitimacy.

In addition to exploring the birth of Jim Crow following the overthrow of chattel slavery and the end of Reconstruction, Alexander meticulously chronicles the repackaging and development of a new system of racial caste in our officially colorblind society following the social and political gains of the Civil Rights Movement.

The disintegration of Jim Crow in the South left millions of whites feeling marginalized, disenfranchised, and resentful over desegregation, affirmative action, and the imposition of new laws and values on “their” society. According to one of his top advisors, Richard Nixon emphasized that “the whole problem is really the blacks. The key is to devise a system that recognizes this while not appearing to” (p. 43).

In an attempt to get Southern whites to break with the Democratic Party—with which they had been largely aligned since Roosevelt’s New Deal—Republican administrations began making racially coded appeals to white voters on issues of “crime,” “law and order,” and “welfare.” This brand of officially colorblind racial politics culminated with President Reagan’s declaration of the current “War on Drugs” in 1982; a “war” waged despite the fact that only two percent of Americans considered illegal drugs to be a major issue at that time. Moreover, contrary to popular belief, drug crime in the early ’80s was on the decline.

When crack-cocaine hit the streets a few years later, however, Reagan administration officials seized the opportunity to zealously promote drug war policies by waging a massive publicity and propaganda campaign highlighting black crack abusers and related violence, which Alexander points out, became a media sensation (pgs. 51-4).

This was, of course, the purpose of the War on Drugs: to put African Americans back in their place on the racial hierarchy. In the ensuing decades, countless billions of federal dollars and advanced weaponry poured into the coffers and arsenals of state and local law enforcement agencies specifically to help launch the drug war in inner cities. Lawmakers joined in the hysteria by passing extreme mandatory minimum sentencing laws, often harshly targeting drugs associated with inner-city blacks rather than middle-class whites.

For his part, President Clinton signed the biggest law enforcement bill in American history and ushered in unprecedentedly cruel “one strike” penalties for ex-felons, banning them from public housing and food stamps for life (pgs. 55-7). Clinton, whom Alexander credits with having done more to create today’s racial caste system than any other president, also oversaw the biggest expansion of the prison system in the history of the United States (p. 56).

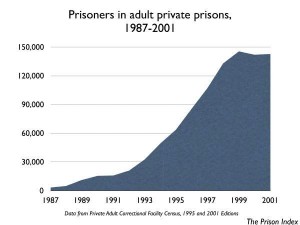

Mass incarceration quickly became a bipartisan set of policies and has since been set on cruise control—if not acceleration—by successive administrations, including the current one (pgs. 238-41).[4] The result? The prison population in the U.S. has increased from 300,000 in 1980 to nearly two and a half million today—by far the biggest prison population of any country in the world, both proportionally and numerically. Crucially, drug offenses account for two-thirds of the increase in federal prisoners and over half of the increase in state prisoners (p. 59).

Rounded up, Locked up, and Locked out

Alexander likens mass incarceration to slavery and Jim Crow on the grounds that each racial caste system functions as a “tightly networked system of laws, policies, customs, and institutions that operate collectively to ensure the subordinate status [of African Americans]” (p. 13).

Mass incarceration, she continues, can be largely understood as functioning in three distinct phases: rounding up men of color, placing them under formal correctional control, and branding them as felons for life (pgs. 180-2). While the author thoroughly and carefully takes into account a great many variables in the book, including history, politics, and legal precedents, it is worth briefly examining here the three distinct phases she highlights.

Police agencies have a tremendous amount of discretion when it comes to enforcing drug laws. Countless studies of policing practices across the country consistently reveal enormous—almost pathological—racial biases against black and brown men. This is especially true with the War on Drugs despite the fact that blacks and Latinos are no more likely to use or sell illegal drugs than their white counterparts.

With the blessing of the courts, police officers are encouraged to stop massive amounts of people—whether driving or walking—to conduct searches, or fishing expeditions, for drugs. The vast majority—upwards of 80 to 90 percent—of those targeted have been people of color.

In cities like New York, this translates into over one thousand Black and Brown men being arbitrarily searched and harassed every day according to the NYPD’s own figures. Many city police departments across the U.S. also keep mass biographical databases of racial minorities irrespective of crime. Rationalized as a means of monitoring “gangs” and “crime,” the databases seek to build profiles on anyone “using slang” or wearing “baggy” pants (read: any person of color).

In Los Angeles and Denver, for example, it has been revealed that the vast majority of Blacks and Latinos residing in these cities were on mass databases of suspected criminals (pgs. 131-4). As Alexander points out, the courts have essentially closed the doors to claims of racial discrimination (absent an admission of racial hatred on the part of officials, McCleskey v. Kemp, 1987, p. 106-9, 189) with the Supreme Court going so far as to declare race to be a legitimate—if not determinative—factor in police discretionary decision making (United States v. Brignoni-Ponce, 1975, pgs. 128-33).

Incarceration rates dramatically reflect racist policing patterns and political priorities. Because the quintupling of the prison population is largely a result of incarcerating Black and Brown drug offenders, the majority of prisoners today are locked up for nonviolent offenses. And despite the fact that Blacks are no more likely (and perhaps less likely) than whites to engage in drug use or sales, in many states Blacks have been sent to prison on drug charges at rates ranging from twenty to nearly sixty times the rate of whites—a pattern which fundamentally holds true for adolescent offenders as well.

In Illinois, for example, Blacks are less than twenty percent of the state’s drug users and sellers, but constitute 90 percent of all incarcerated drug offenders. As a nation, whites are the overwhelming majority of drug users and sellers yet the vast majority—75 percent—of all drug offenders sent to prison are Black or Latino (pgs. 96-7).

It is no surprise then that one in every three young Black men in America is either locked up or on probation or parole; nationwide, the figure is nearly 50 percent when those who have been permanently labeled as felons are included.[5] It should be emphasized that the status of those on probation and parole—especially the latter—is equivalent to having no civil rights; often times the slightest infraction—for example, missing an appointment or failing to find a job—is enough for the state to tear the individual from his family and community and lock him in a cage for months or even years (p. 93).

For many inner-city communities, prison has become the rule rather than the exception. To cite just one example, in Washington DC, three out of every four young Black men—irrespective of class—can expect to be incarcerated (p. 159).

At the current rate of incarceration, one out of every three Black male babies born at the turn of the 21st century will end up in prison.[6] Today, due largely to the mass incarceration of Black men, an African-American child is less likely to be raised by both parents than a Black child born during slavery (p. 175) and almost ten times more likely than white children to have a parent incarcerated.[7]

Once branded a felon, individuals are permanently relegated to a second class status. Drug felons specifically are banned from receiving subsidized loans for college. All felons are banned from public housing and can be legally discriminated against in private housing. They are also required by law to “check the box” on job applications and employers are entitled to legally discriminate against them. In fact, surveys show the vast majority of employers admit that they will not consider hiring a felon.

Barred from affordable housing, educational opportunities, and shut out of the job market, felons also lose the right to eat; they are banned from receiving food stamps for life. In addition to losing the right to possess firearms, felons are completely excluded from serving on juries; because of this, fully 30 percent of black men in America have been automatically excluded from serving on juries (p. 119).

This is in addition to Supreme Court rulings which allow courts to, in practice, systematically exclude Blacks from juries for admittedly “silly” and “superstitious” reasons which serve as legal cover for maintaining the all-white jury, which is and always has been a staple institution in American life (pgs. 188-9). Perhaps worse yet, felon disenfranchisement laws deny the right to vote to millions of African Americans across the country. In fact, as of 2004 more Black men were disenfranchised than in 1870, which was the year the fifteenth amendment was ratified which outlawed the denial of voting rights to people on the basis of race (p. 175).

Racial Caste: Defining What it Means to be Black

Because mass incarceration and felony branding policies have been unjustly directed primarily at African Americans and other people of color, Alexander argues that the current system amounts to a restructuring of racial caste in America. This charge is not without merit; in cities and states where African Americans are highly concentrated, huge majorities of Black men have been locked up and/or labeled as felons for life—mostly for minor, nonviolent drug offenses—making it perfectly legal to discriminate against them in all of the same ways that the Jim Crow system discriminated against their parents and grandparents several decades ago.

In Chicago, for example, fully 80 percent of the Black male workforce has been branded felons for life. The criminalization of Black men in Chicago—and Black men in urban America generally—is, of course, largely a phenomenon of the War on Drugs; since 1985 the number of Black men incarcerated for nonviolent drug offenses in Chicago has increased by nearly 2,000 percent (pgs. 183-5, 191).

The trend generalizes across the U.S.; as of the year 2000, on a national level African American incarceration for drug offenses represented a 26-fold increase since 1985 (p. 96). Much in the same way that segregation and ghettoization of African Americans in the North was the result not of market forces nor human nature but rather the outcome of specific federal and local policies designed for those ends, mass incarceration is the result of deliberate policy choices aimed at strengthening the historical racial order in America, ensuring that African Americans remain in a subordinate and stigmatized position on the social and racial hierarchy.[8]

The policies of mass incarceration—coupled with paralleled, racialized political and media campaigns—in recent decades have served to define in racial terms what it means to be a criminal. As Alexander points out, every system of racial caste in America has had as its primary function, the ability to define the meaning of race in its time (pgs. 192-5).

During slavery, to be Black was to be a slave and to be Black under Jim Crow was to be a second class citizen. In the age of mass incarceration, to be Black—and this is especially true for men—is to be a criminal (pgs. 192-5). In our society, the racialization of what it means to be a criminal amounts to the stigmatization of African Americans as a group.

The War on Drugs has been the primary vehicle for creating both the on-the-ground reality as well as, in part, the ideological foundations for racial caste in an America that is officially colorblind; although all studies show that the majority white population is just as likely—perhaps even more so—to engage in drug use and sales, Black men—and to a lesser degree, Latinos—are the ones who have been targeted, incarcerated, and branded as criminals en masse.

While whites who have been branded as felons surely experience the stigma associated with incarceration, their stigma is by no means a racial stigma; the term “white crime” is unfathomable and nonexistent while “black criminal” is nearly redundant (p. 193). In fact, Alexander insists that the fact that blacks “only” comprise 80 or 90 percent of those incarcerated for drug offenses in some states—instead of 100 percent—actually serves to reinforce the legitimacy of racial caste in an officially colorblind society; the exception that justifies the rule (pgs. 198-9).

As a system of racial caste, mass incarceration doesn’t just apply to those officially branded as felons. “Just as African Americans in the North were stigmatized by the Jim Crow system even if they were not subject to its formal control,” Alexander writes, “Black men today are stigmatized by mass incarceration—and the social construction of the “criminalblackman”—whether they have ever been to prison or not” (p. 194).

This is evidenced in part by dominant media and cultural narratives, institutionalized (and legalized) racial profiling, and police efforts to build mass databases of “suspected criminals” which contain information almost exclusively on racial minorities who have often done nothing criminal at all aside from having been born to Black and Brown parents.

In addition to the numerous studies showing that most white Americans see crime in racial (nonwhite) terms, studies conducted by Princeton University also reveal that white felons fresh out of prison are more likely to get hired for jobs than equally qualified black men with no criminal record.[9]

African American men without criminal records are more ostracized and widely perceived as being more criminal than white men who have actually been convicted of felony crimes. That is how deeply Black people have been stigmatized as criminals and social pariahs in our society. Whole Black communities have been stigmatized by the presence of felons in their midst and Black men have, Alexander aptly observes, become “the new untouchables” (p. 194).

Worse yet, Alexander contends that the racial solidarity which existed to a substantial degree among Blacks during Jim Crow has been significantly destroyed by mass incarceration: “[T]he shame and stigma of the ‘prison label’ is, in many respects, more damaging to the African American community than the shame and stigma associated with Jim Crow. The criminalization and demonization of black men has turned the black community against itself, unraveling community and family relationships, decimating networks of mutual support, and intensifying the shame and self-hate experienced by the pariah caste” (p. 17).

The campaign of drug criminalization in recent decades begs comparisons to the birth of Jim Crow in the late nineteenth century. Following Reconstruction, white Southerners sought to reestablish the white supremacist racial order but were constrained in doing so by new realities imposed by the federal government, including the abolition of chattel slavery.

Lawmakers instead chose to criminalize minor offenses which were often colorblind on paper, such as loitering, vagrancy, “using obscene language,” and so forth, in order to establish pretexts for imprisoning black men and forcing them back on to the plantations via contracted prison labor—a vast system of re-enslavement through mass incarceration which was, in many respects, worse than traditional slavery.[10]

While Jim Crow eventually included many laws explicitly discriminating on the basis of race, a major part of this racist system centered on how seemingly race-neutral laws were enforced and who was targeted. This was true for disenfranchising Black voters as well. Because the federal government outlawed denying the vote to citizens on the basis of race, southern officials introduced ostensibly colorblind literacy tests and poll taxes, but everyone knew that the laws were aimed at Black folks and were almost exclusively enforced accordingly to achieve that end.

The War on Drugs is similar; initiated largely by the federal government, the drug war policies have criminalized minor offenses and activities—drug use and sale—which exist in all human societies and exist equally across racial lines in America, and took care to enforce these laws overwhelmingly against blacks and other racial minorities.

The New Jim Crow does an excellent job of dispelling common myths often cited to explain in colorblind terms the reasons for the mass incarceration of African Americans. In addition to setting the record straight on the prevalence of drug activity along racial lines, Alexander also explains that the War on Drugs has not been waged in poor communities of color because of higher rates of violent crime among poor blacks.

Comparatively speaking, higher rates of violent crime in black communities is independent of drug activity and has very little to do with the recent prison boom; citing William Julius Wilson’s When Work Disappears, Alexander notes that rates of violent crime are directly related to concentrated joblessness.[11] When the racial disparity in joblessness is accounted for, violent crime rates for blacks and whites are virtually indistinguishable (p. 50).

Moreover, the drug war is expressly not aimed at reducing violent crime or even going after drug kingpins; the main purpose is to amass high volumes of arrests and obtain as many convictions as possible—the vast majority of which are possession charges for small amounts of marijuana and other drugs.

How Does it Feel to be a Problem?

Like slavery and Jim Crow, mass incarceration is all but invisible to whites in the sense that it appears completely normal and doesn’t directly affect most white communities.[12] In fact, in recent years it has become almost cliché—though indeed accurate—to observe that the number of Black men in prisons has drastically eclipsed the number of Black men in college; before the current drug war, in 1980, however, Black men in college outnumbered Black men in prison by a ratio of three to one.[13]

Consider the militarization of policing, paramilitary-style sweeps of entire neighborhoods, routine violence and police brutality, constant, arbitrary, and humiliating searches and invasions: such a violent campaign of dehumanization and oppression could never feasibly target white drug users and dealers on college campuses and in the suburbs as it has Black and Brown citizens in the inner city (pgs. 199-202).

Yet whites overwhelmingly take mass incarceration and racial caste—though not by those names—for granted, as if the wholesale imprisonment and stigmatization of Blacks is something natural or inevitable; after all, crime—and therefore, mass incarceration—is a Black problem.

In The Souls of Black Folk, written in 1903, W.E.B. Dubois describes the prevailing attitude of whites towards African Americans in the terms of an implicit question whites often leveled at blacks on the issue of race: “How does it feel to be a problem?”[14]

Today when whites talk about getting “tough on crime” and when they call on African American leaders—or when such “leaders” do so voluntarily—to take the Black community to task for alleged cultural deficiencies supposedly at the heart of African American social and economic problems, they are essentially saying the same thing as the whites of Dubois’ era: “How does it feel to be a problem?”

The “sprinkling” of a select few of people of color in universities, the government, corporations, television—and even in the White House—helps to perpetuate the myth of racial equality and “Black progress”—a loaded and historically insulting term—in post-Civil Rights era America. While nobody can deny that great gains have been achieved as a result of popular activism led by African Americans in the 1950s and ’60s, the painful reality is that in many key respects, the Black community in America is no better off—and in some respects, worse off—than it was in 1968 when Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated (pgs. 233-6).

Schools are more segregated and unequal today than they were in 1950; residential housing is more segregated in the Midwest and Northeast than in the South.[15] Poverty rates in the black community remain high and have changed little, especially if prisoners are included.

Among Black children, poverty rates have actually increased, according to Alexander (p. 233). Joblessness continues to be disproportionately high for African Americans, notably young Black men, of which one in three are unemployed (p. 149). For those who don’t complete high school, the rate of joblessness soars to 65 percent (p. 149). Rampant police brutality in the Black community continues to persist. And of course, incarceration of Black men—and Black women for that matter—is at all time, astronomical highs.

In The New Jim Crow, Michelle Alexander brilliantly and systematically lifts from readers’ eyes the veil of colorblind rhetoric, affirmative action, and tall tales of progress and equality in America and urges us to face the racial nightmare and human rights catastrophe that has been taking place on our watch.

While impeccably documented and full of careful legal analysis, this is not a book so much for lawyers as it is for regular people who care about justice and freedom. The New Jim Crow is above all, a movement-building book. And considering what is at stake, nothing short of a militant, mass based civil rights style movement can hope to dismantle mass incarceration and racial caste in America once and forever.

Max Kantar is an independent writer and Michigan-based human rights activist. He can be reached at maxkantar@gmail.com.

Notes.

[1] Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (New York: The New Press, 2010). References to specific information in the book throughout this review will be cited parenthetically in the text.

[2] W.E.B. Dubois, The Souls of Black Folk 3rd edition (Cambridge: University Press, 1903).

[3] This is if you include black men in both prison and jail in the US. The rate is about three and a half times higher than apartheid South Africa if incarceration rates only include those in prisons. See William J. Sabol, Todd D. Minton, and Paige M. Harrison, “Bureau of Justice Statistics: Prison and Jail Inmates at Midyear 2006″ (Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, June 2007), NCJ217675, p. 9, Table 14.

[4] On Obama’s presidential record on these matters, see “The Obama Administration’s 2011 Budget: More Policing, Prisons, and Punitive Policies,” Justice Policy Institute, February 2010, http://www.justicepolicy.org/images/upload/10-02_FAC_FY2011Budget_PS-JJ-AC-BB-DP.pdf (accessed November 5, 2010).

[5] Marc Maurer and Tracy Huling, “Young Black Americans and the Criminal Justice System: Five Years Later” (Washington DC: The Sentencing Project, 1995).

[6] Gary Younge, “30% of black men in US will go to jail,” The Guardian, August 19, 2003.

[7] Bureau of Justice Statistics, “Incarcerated Parents and Their Children” (Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, August 2000).

[8] Regarding government policies which created segregation and ghettoization in the North, see Douglas Massey and Nancy Denton, American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of the Underclass (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993).

[9] Devah Pager and Bruce Western, “Race at Work: Realities of Race and Criminal Record in the NYC Job Market” (Princeton University, December 9, 2005). For online access see http://www.princeton.edu/~pager/).

[10] Douglas A. Blackmon, Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black People in America from the Civil War to World War II (New York: Anchor Books, 2009).

[11] William Julius Wilson, When Work Disappears: The World of the New Urban Poor (New York: Vintage Books, 1997).

[12] There is one major exception here: in recent decades, many prisons have been built in rural, predominantly white towns across America. These towns have a huge stake in mass incarceration due to the amount of jobs that prisons bring to these communities. Nonetheless, the point remains the same: prison is not a part of life for many white families, whereas in many African American communities one would be hard pressed to find families without someone currently or recently incarcerated. See Alexander, New Jim Crow, 188.

[13] Fox Butterfield, “Study Finds Big Increase in Black Men as Inmates Since 1980,” New York Times, August 28, 2002.

[14] Dubois, The Souls, 1-2.

[15] Gary Orfield, “Reviving the Goal of an Integrated Society: A 21st Century Challenge,” The Civil Rights Project, UCLA, January 2009, http://civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/ (accessed November 5, 2010); Jonathon Kozol, The Shame of the Nation: The Restoration of Apartheid Schooling in America (New York: Random House, 2005); “American Urban Segregation,” BlackDemographics.com, http://www.blackdemographics.com/geography.html (accessed November 5, 2010).

Justice Strategies Report: “Children on the Outside: Voicing the Pain and Human Costs of Parental Incarceration”Expert analysis and first-hand testimony from children, parents and care-givers uncovers the devastating impact of parental incarceration on youth and the broader community and points to smart approaches to reduce prison populations, assist children, and improve public safety.

JUSTICE STRATEGIES CONTACT: Matt Nelson, mattnelsoncoc@gmail.com, (414) 721-6630National–Losing a parent to a prison sentence resembles the trauma of losing a parent to death or divorce and is compounded by social stigma and limited public support, according to new research detailing parental incarceration’s impact on children. “Children on the Outside: Voicing the Pain and Human Costs of Parental Incarceration,” a new report from Justice Strategies, a nonprofit research organization pursuing more humane and cost-effective approaches to criminal justice and immigration law enforcement, provides first-hand accounts of the harm experienced by some of the 1.7 million minor children with a parent in prison, a population that has grown with the explosion of the U.S. prison population.

“When they do time we also do time. Just because we’re not in there doesn’t mean we don’t do time. Because you’re not with us, we also do time,” explained Araya, a teen girl with an incarcerated father.

The report details the challenges faced by children of incarcerated parents, whose experience of grief and loss is compounded by economic insecurity, family instability, a compromised sense of self-worth, attachment and trust problems, and social stigmatization when their parents are incarcerated. The report also outlines the ways in which parental incarceration can influence negative outcomes for youth, including mental health problems, possible school failure and unemployment, and antisocial and delinquent behavior.

“Too often, society dismisses the children of incarcerated parents as future liabilities to public safety while overlooking opportunities to address the pain and trauma with which these children struggle,” said Patricia Allard, co-author of the report. “It is by tackling the psychological and emotional trauma head-on that we not only aid these children to grow into our future mothers, fathers, taxpayers and workers, but also ensure more stable and thriving communities.”

As with the punitive consequences of our mandatory sentencing and mass incarceration policies, the impact of parental incarceration falls disproportionately on children of color. African American children are seven times and Latino children two and half times more likely to have a parent in prison than white children. The estimated risk of parental imprisonment for white children by the age of 14 is one in 25, while for black children it is one in four by the same age.

Prepared by Patricia Allard and Judith Greene, “Children on the Outside” urges a shift from failed tough on crime policies toward a public health and safety strategy that includes evidence-based treatment options and reducing reliance on incarceration. Additionally, the report outlines concrete tactics that can help to moderate the negative impact of parental incarceration on children and points to existing and promising approaches for cost-effective criminal justice policies that promote community health and safety. To illustrate this point the report compares New York, which has downsized prisons through drug reform, saved money, and seen larger decreases in crime with Alabama, a state with higher incarceration rates.

“States have long struggled with the enormous fiscal expense of prisons, but now we’re finding an entirely new human cost that has been previously overlooked,” continued Allard. “When it comes to wasteful policies that bloat prisons without improving safety, we can’t afford to look the other way. We need to find ways to care for the young people who have already lost their parents to prison, and more importantly, stop needlessly separating parents from children when other safe options exist.”

Key findings from the report include:

The U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) estimated that by 2007, more than half (53 percent) of the 1.5 million prisoners in the U.S. were parents of minor children – translating into more than 1.7 million children with an incarcerated parent. This represents an increase of 80 percent since 1991.

Nearly one quarter of these children are age four or younger, and more than a third will become adults while their parent remains behind bars.

Parental imprisonment is associated with:

-

- Three times the odds that children will engage in antisocial or delinquent behavior (violence or drug abuse).

-

- Negative outcomes as children and adults (school failure and unemployment).

-

- Twice the odds of developing serious mental health problems.

-

Data compiled at BJS shows that the acute problem of racial disparity behind bars is also reflected among the children of incarcerated parents, with black children seven and a half times more likely than white children to have a parent in prison.

While only one in 25 white children born in 1990 had a parent who was imprisoned, one in four black children born that year had a parent imprisoned.

To receive an embargoed copy of the full report or request an interview with the report’s authors or participants, contact Matt Nelson at: mattnelsoncoc@gmail.com, (414) 721-6630.

About the authors:

PATRICIA ALLARD is Deputy Director of the Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network. For the past ten years she has worked in the United States advocating for criminal justice and drug policy reform — with a particular emphasis on the needs of low-income women and women of color, at the Sentencing Project and the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University Law School.

JUDITH GREENE is a criminal justice policy analyst and a founding partner in Justice Strategies. Over the past decade she has received a Soros Senior Justice Fellowship from the Open Society Institute, served as a research associate for the RAND Corporation, as a senior research fellow at the University of Minnesota Law School, and as director of the State-Centered Program for the Edna McConnell Clark Foundation. From 1985 to 1993 she was Director of Court Programs at the Vera Institute of Justice.

Perpetrators and enablers of torture in the U.S.

http://sfbayview.com/2009/perpetrators-and-enablers-of-torture-in-the-u-s/

Anthony Hall, 18, spends 23 hours per day in this cell in the supermax prison in Boscobel, Wisc. Judging from letters to the Bay View from prisons throughout the country, Boscobel seems to be one of the worst for Black prisoners. Prison officials there have often refused to deliver the Bay View to subscribers on the excuse that it would “incite a riot.” – Photo: Andy Manis, AP

Posted by blockreportradio On November 1, 2009 @ 9:50 am In Prison Stories (see link to Block Report Radio at right of this site)

During the past 25 years I’ve spent a lot of time with survivors of torture, men and women enduring long term solitary confinement in California’s prisons. They are the most urgent victims of U.S. mass incarceration with its overcrowded facilities and policy of incapacitation, not rehabilitation.

Those thousands held in solitary for years on end report the expected classic symptoms of psychic disturbance, mental deterioration and social disruption. As described by various penal psychiatric experts, the symptoms of this syndrome include massive free-floating anxiety, hyperresponsiveness to external stimuli, perceptual distortions and hallucinations, a feeling of unreality, difficulty with concentration and memory, acute confusional states, the emergence of primitive aggressive fantasies, persecutory ideation, motor excitement and violent destructive or self-mutilatory outbursts.

The degrading conditions produce behaviors ranging from fights among prisoners to assaults on staff, assaults by staff, excrement throwing, self mutilation and contract killings. Isolation tears apart family and friendship ties, creating social dislocation.

In California there are about 4,000 men and women held in the state’s supermax facilities, called Security Housing Units, including 600 serving SHU terms in Administrative Segregation. That is 2.5 percent of the total population of 160,000.

The regime in SHU is a 23.5 hour per day lockdown in the 8’ x 10’ cell with no communal activities aside from small group exercise yards for some. There is no work, no school, no communal worship and meals are eaten in cell.

TVs and radios must be purchased, so the poor have none. Visits are noncontact, behind glass and limited to one or two hours on each weekend visit day. Each prisoner must submit to being handcuffed behind the back in order to exit the cell. Leg iron hobble chains are commonly used.

More than 50 percent of the men in SHU are assigned indeterminate terms there because of alleged gang membership or activity. The only program that the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCr) offers to them is to debrief.

The single way offered to earn their way out of SHU is to tell departmental gang investigators everything they know about gang membership and activities, including describing crimes they have committed. The department calls it debriefing. The prisoners call it “snitch, parole or die.” The only ways out are to snitch, finish the prison term or die. The protection against self incrimination is collapsed in the service of anti-gang investigation.

CDCr asserts that the lockdown and snitch policy are required for the safety and security of the institution. Having legitimate penalogical purpose, the SHU program is deemed worth any harm done to the prisoners.

California prisons continue to have a high rate of assaultive incidents among prisoners and from prisoners to staff. There is no proof or even any study that demonstrates that these measures are effective anti-gang measures. They appear to be no more useful than previous brutalities like that unleashed at Corcoran prison more than a decade ago.

Between 1988 and 1995, CDCr ran a program at the Corcoran SHU called the Integrated Yard Policy. Rival gang members were deliberately mixed together in small group exercise yards. The prisoners had to fight, and fight well or be punished by their own gangs.

When the fights occurred, guards were required to fire first anti-riot guns and then assault rifles at the combatants. Seven prisoners were killed and hundreds wounded. The program of beating prisoners down into the concrete with gunfire resulted in bigger, stronger gangs with new martyrs and heroes.

Mayhem and violence was added to the prison social system by departmental policy. No CDCr official has ever been held accountable or even assigned responsibility for what was know at Corcoran as the gladiator days. Line staff brought to trial by the U.S. Department of Justice avoided criminal convictions by proving that they were just following orders.

There are four prisons in California with SHUs: Corcoran, Pelican Bay and Tehachapi for men and Valley State Prison for Women. Only a few women have ever been given a SHU term for gang activity.

All those identified as gang members by the administrative kangaroo court serve SHU terms without end. The only way out is to debrief, to testify against oneself to prison rules violations and crimes.

Prisoners have found it very hard to attack the abuses in the SHU, even though the U.S. is under the jurisdiction of the U.N. Convention Against Torture (CAT). The U.S. states reservations to the treaty asserting that the U.S. Constitution and body of law are all that is required to satisfy the obligations of CAT.

But the 1995 Prison Litigation Reform Act (PLRA) that prohibits a prisoner bringing action for mental or emotional injury without prior showing of physical injury is one law that violates CAT. The U.N. Committee on Torture expressed concern that by disallowing compensation for psychic abuse the PLRA is out of compliance with CAT.

Under CAT, torture includes “any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted.” But the U.S. 1990 reservations to CAT were designed specifically to allow solitary confinement, as the reservations state that mental pain and suffering must be prolonged, be tied to infliction or threats of infliction of physical pain, the result of drugging or the result of death threats.

Despite SHU confinement without end to attempt to control gangs, prison gangs thrive in California’s prisons. The gang leadership predictably uses the snitch sessions to falsely target their rivals, or just recruit new members. Just as we have seen in U.S. anti-terror investigations, information derived from coercion is often unreliable.

Using indeterminate total lockdown to extract confessions is torture by international standards, as is the use of prolonged solitary confinement. U.S. prison officials order by rule the torture of prisoners. One in 31 adults in the U.S. is under the supervision of the criminal detention system – jail, prison, probation or parole – with 2.5 million behind bars.

Prisons dominate the lives of poor communities and communities of color and are ignored by affluent white America. One in 11 African-Americans and one in 27 Latino-Americans are under penal jurisdiction. Prisoners damaged by incarceration are returning to communities increasingly less able to absorb them.

The 2005 census found that severe poverty increased 26 percent more than the overall growth in poverty. In 2002, 43 percent of the nation’s poor were living in severe poverty, the highest rate since 1975.

Torture has always served more to beat down a population than to extract reliable information. The unstated goal is to incapacitate and marginalize the dangerous poor who are locked out of America’s opportunity and riches. The routine even banal nature of torture in U.S. prisons enables torture to be acceptable, and informs our failing strategies of dealing with any opposition by using brute force.

A more useful way to undermine and blunt prison gangs would be to provide programs and procedures that enliven the community of prisoners with rehabilitative activity making them too busy and too hopeful to become involved. Drug and mental health treatment and education and vocational training rather than enforced idleness and despair will help change the culture of the prison yard from a battleground to a place for personal and social renewal. To be successful at a renewal behind bars, a revitalization of our poor communities is desperately needed.

I’ll never forget my visit to several prisons in the United Kingdom a number of years ago. I toured one of their high security units housing eight of the 40 men out of 75,000 considered too dangerous or disruptive to be in any other facility. The men were out of their cells at exercise or at a computer or with a counselor or teacher.

The goal was to get them back on mainline through rehabilitation, not terror. With embarrassment, the host took us to the one cell holding the single individual who had to be continuously locked down and cuffed and hobbled before exit from his cell. I was equally embarrassed to tell our guide that this is how 2.5 percent of U.S. prisoners are routinely treated.

Corey Weinstein, MD, CCHP, is a physician, a Certified Correctional Health Professional and a renowned advocate for justice behind enemy lines. He can be reached at coreman@igc.org .

Minister JR interviews Karima al-Amin, wife of political prisoner Imam Jamil al-Amin (H. Rap Brown), on Block Report Radio

| ||||

| Go to: http://www.blockreportradio.com/radio-mainmenu-27/990-karima-al-amin.html |

The Minister of Information JR interviews Karima Al-Amin, the lawyer and wife ofpolitical prisoner Imam Jamil Al-Amin, about his case and his torturous incarceration in Florence Colorado, which we call the Abu Ghraib-like prison within Amerikkka. (See other articles in VOD archives and prison page re: Imam al-Amin and the FBI assassination of Imam Luqman Abdullah, head of the Masjid el-Haqq mosque in Detroit, on Oct. 28, 2009. Karima al-Amin speaks in the radio interview of how the government is targeting Masjids across the country, largely because of their work in reducing gang violence, drug trafficking and prostitution in their neighborhoods.) |

MARILYN BUCK

MARILYN BUCK

By Mumia Abu-Jamal

For nearly 30 long, tortuous years, Marilyn Buck was a political prisoner of the state, a captive in the federal prison system for her role in the liberation of former Black Panther Assata Shakur.

She wrote gripping lines of radical poetry, often about the lives and plights of her fellow imprisoned women, as well as of prisoners who were active in the Black Freedom and Nationalist movements.

For example, back in 2000 she wrote “Black August,” an excerpt of which follows:

Would you hang on a cliff’s edge

sword-sharp, slashing fingers

while jackboot screws stomp heels

on flesh peeled bones

and laugh

“Let go! Damn you, die!”

could you hold on 20 years, 30 years?

brave Black brothers buried

in U.S. concentration camps

they hang on

Black light shining in torture

chambers

Ruchell, Yogi, Sundiata, Sekou

Warren, Chip, Seth, Herman, Jalil

and more they resist

Black August. . . .

Marilyn wrote that poem in 2000.

She was released in 2010, and recently passed away from the ravages of cancer.

Marilyn Buck was imprisoned so long because of her support of the Black liberation movement, which made her a traitor, of sorts, to the White Nation. Like John Brown, she fought to free the unfree.

Her spirit of resistance never left her.

Marilyn was 62.

ONE BORN EVERY MINUTE—Michigan contracts with private prison corporation Geo Group

By Dr. Publico

While we’ve been distracted by the mid-term elections, the business of America—business—continues. They never miss a beat…

The Democratic governor of Michigan teamed up with her Republican counterpart in California for another magic-mirrors fix to their respective budgetary problems. This time it’s private prison profiteering.

The Geo Group (formerly Wackenhut), one of the largest private prison corporations in the world, made a deal with Michigan to use their mothballed North Lake Correctional Facility (Baldwin) to house 2600 California prisoners. Michigan expects to get 450 local jobs.

However, the Michigan taxpayers will also have to foot the bill for some considerable undisclosed “renovations” thru Granger Construction, Lansing, Neumann-Smith Architects, Southfield, MI, and the Firestone Corp.

California, which currently expends some $125/day per prisoner, will pay Geo Group $60 million/yr. on a 3-yr contract. That comes to about $65/day…a considerable savings to that state. And what do we get? That is, Michigan, the prisoners, and their respective communities? More row to hoe … count on it.

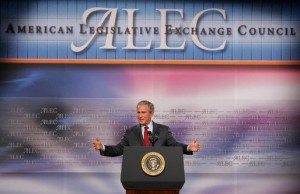

These “fixes” don’t just happen on their own. For Jerry Maguire’s, “Show me the money!” we don’t have very far to look: The American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) was created in 1973. It’s a conservative bill-mill of state legislators and private industry whose purpose is to create “model legislation” that in turn creates profit for their members.

Basically, they target government business (without the public responsibility, of course). About 1/3rd of the state legislators in the US (some 2,400) are members. While they pay a $100 fee for 2-yr memberships, they receive $$thousands in “contributions” from private industry in turn. Many of the legislative members of ALEC have gone on to become governors and representatives in Congress. Quite simply, it’s a revolving criminal conspiracy.

ALEC models itself much after the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM) created in 1895 as a brain trust for the capital parties (increasingly Republican), and as a counterweight to the development of worker unions, which they consider to be expressions of “despotism, tyranny, and slavery.”

ALEC’s legislation is a what’s what of reactionary laws that increase criminalization, draconian sentencing, and opposition to any expenditure of public money where there is a possibility of it being channeled to private profit. To wit: Public healthcare, education, immigration, criminal justice, Social Security, Medicare, and any other form of the “liberal social agenda,” which they utterly oppose.

Examples include many of the drug laws they’ve sponsored, so-called “truth in sentencing” (the elimination of good-time, parole, etc.), “3-strikes-you’re out” legislation, and the elimination of Pell Grants for prisoners. Basically, whatever increases the number of prisoners and the time they serve is fodder for profit.

The very crises that Michigan, California, the other states and the federal gov’t are facing, budget-wise, were in fact largely created by ALEC and their conservative minions. To profit from the current contract, they’ll have the California officials cherry-pick the prisoners. They’ll be mostly first-offender, non-violent types who essentially abide by the system. (In other words, non-criminals—except in the statutory sense…which ALEC’s legislation created to begin with.)

The prisoners will have minimal housing, education, medical, dental, recreation, rehab programs (except for the faith-ministries who are also partnered with ALEC), and they’ll be almost 2,000 miles from home, virtually eliminating visits. Further, staff will have minimal pay, benefits and training. In the long term, prisoners will return to their respective communities no better than when they left–if not worse. Abuse begets abuse (which, of course, suits business just fine).

And the crème de la crème? Ahh, here’s the Gordon Gekko chatter they feed their financial co-conspirators…excuse me…I mean “stockholders”: “We’ll be having the state build us the facilities and the gov’t sanctioning prisoner neoslavery labor while we partner with Michigan business to produce goods cheaply by undercuting unions and wages!” Tickles your “tough on crime” bone, eh? Far more free-world jobs will be lost than gained.

Of course, this is still a sideshow for GEO. They and ALEC are primarily focused on immigrant workers and their further criminalization. Given the numbers (over 400,000), that’s the super-$$ ticket that’s driving their current model legislation machinery. Where do you think SB-1070 out in Arizona (and currently running thru the legislatures in over 30 other states) came from?

You see, the problem is people simply don’t follow the money… “Tough on crime”? LOL. They’re in the business of creating crime and profit from what they create. Period.

As Gordon Gekko in the Wall Street movies would say: Suckers!

One of the founders of ALEC, John Engler, went on to become a governor of Michigan and is today the president of NAM.

PRISON ECONOMICS HELP DRIVE ARIZONA IMMIGRATION LAW

by Laura Sullivan, NPR

October 28, 2010Last year, two men showed up in Benson, Ariz., a small desert town 60 miles from the Mexico border, offering a deal.

Glenn Nichols, the Benson city manager, remembers the pitch.

“The gentleman that’s the main thrust of this thing has a huge turquoise ring on his finger,” Nichols said. “He’s a great big huge guy and I equated him to a car salesman.”

What he was selling was a prison for women and children who were illegal immigrants.

“They talk [about] how positive this was going to be for the community,” Nichols said, “the amount of money that we would realize from each prisoner on a daily rate.”

But Nichols wasn’t buying. He asked them how would they possibly keep a prison full for years — decades even — with illegal immigrants?

“They talked like they didn’t have any doubt they could fill it,” Nichols said.

That’s because prison companies like this one had a plan — a new business model to lock up illegal immigrants. And the plan became Arizona’s immigration law.

Behind-The-Scenes Effort To Draft, Pass The Law

The law is being challenged in the courts. But if it’s upheld, it requires police to lock up anyone they stop who cannot show proof they entered the country legally.

When it was passed in April, it ignited a fire storm. Protesters chanted about racial profiling. Businesses threatened to boycott the state.

Supporters were equally passionate, calling it a bold positive step to curb illegal immigration.

But while the debate raged, few people were aware of how the law came about.

NPR spent the past several months analyzing hundreds of pages of campaign finance reports, lobbying documents and corporate records. What they show is a quiet, behind-the-scenes effort to help draft and pass Arizona Senate Bill 1070 by an industry that stands to benefit from it: the private prison industry.

The law could send hundreds of thousands of illegal immigrants to prison in a way never done before. And it could mean hundreds of millions of dollars in profits to private prison companies responsible for housing them.

Arizona state Sen. Russell Pearce says the bill was his idea. He says it’s not about prisons. It’s about what’s best for the country.

“Enough is enough,” Pearce said in his office, sitting under a banner reading “Let Freedom Reign.” “People need to focus on the cost of not enforcing our laws and securing our border. It is the Trojan horse destroying our country and a republic cannot survive as a lawless nation.”

But instead of taking his idea to the Arizona statehouse floor, Pearce first took it to a hotel conference room.

It was last December at the Grand Hyatt in Washington, D.C. Inside, there was a meeting of a secretive group called the American Legislative Exchange Council. Insiders call it ALEC.

It’s a membership organization of state legislators and powerful corporations and associations, such as the tobacco company Reynolds American Inc., ExxonMobil and the National Rifle Association. Another member is the billion-dollar Corrections Corporation of America — the largest private prison company in the country.

It was there that Pearce’s idea took shape.

“I did a presentation,” Pearce said. “I went through the facts. I went through the impacts and they said, ‘Yeah.’”

Drafting The Bill

The 50 or so people in the room included officials of the Corrections Corporation of America, according to two sources who were there.

Pearce and the Corrections Corporation of America have been coming to these meetings for years. Both have seats on one of several of ALEC’s boards.

And this bill was an important one for the company. According to Corrections Corporation of America reports reviewed by NPR, executives believe immigrant detention is their next big market. Last year, they wrote that they expect to bring in “a significant portion of our revenues” from Immigration and Customs Enforcement, the agency that detains illegal immigrants.

In the conference room, the group decided they would turn the immigration idea into a model bill. They discussed and debated language. Then, they voted on it.

“There were no ‘no’ votes,” Pearce said. “I never had one person speak up in objection to this model legislation.”

Four months later, that model legislation became, almost word for word, Arizona’s immigration law.

They even named it. They called it the “Support Our Law Enforcement and Safe Neighborhoods Act.”

“ALEC is the conservative, free-market orientated, limited-government group,” said Michael Hough, who was staff director of the meeting.

Hough works for ALEC, but he’s also running for state delegate in Maryland, and if elected says he plans to support a similar bill to Arizona’s law.

Asked if the private companies usually get to write model bills for the legislators, Hough said, “Yeah, that’s the way it’s set up. It’s a public-private partnership. We believe both sides, businesses and lawmakers should be at the same table, together.”

Nothing about this is illegal. Pearce’s immigration plan became a prospective bill and Pearce took it home to Arizona.

Campaign Donations

Pearce said he is not concerned that it could appear private prison companies have an opportunity to lobby for legislation at the ALEC meetings.

“I don’t go there to meet with them,” he said. “I go there to meet with other legislators.”

Pearce may go there to meet with other legislators, but 200 private companies pay tens of thousands of dollars to meet with legislators like him.

As soon as Pearce’s bill hit the Arizona statehouse floor in January, there were signs of ALEC’s influence. Thirty-six co-sponsors jumped on, a number almost unheard of in the capitol. According to records obtained by NPR, two-thirds of them either went to that December meeting or are ALEC members.

That same week, the Corrections Corporation of America hired a powerful new lobbyist to work the capitol.

The prison company declined requests for an interview. In a statement, a spokesman said the Corrections Corporation of America, “unequivocally has not at any time lobbied — nor have we had any outside consultants lobby – on immigration law.”

At the state Capitol, campaign donations started to appear.

Thirty of the 36 co-sponsors received donations over the next six months, from prison lobbyists or prison companies — Corrections Corporation of America, Management and Training Corporation and The Geo Group. By April, the bill was on Gov. Jan Brewer’s desk.

Brewer has her own connections to private prison companies. State lobbying records show two of her top advisers — her spokesman Paul Senseman and her campaign manager Chuck Coughlin — are former lobbyists for private prison companies. Brewer signed the bill — with the name of the legislation Pearce, the Corrections Corporation of America and the others in the Hyatt conference room came up with — in four days.

Brewer and her spokesman did not respond to requests for comment.

In May, The Geo Group had a conference call with investors. When asked about the bill, company executives made light of it, asking, “Did they have some legislation on immigration?”

After company officials laughed, the company’s president, Wayne Calabrese, cut in.

“This is Wayne,” he said. “I can only believe the opportunities at the federal level are going to continue apace as a result of what’s happening. Those people coming across the border and getting caught are going to have to be detained and that for me, at least I think, there’s going to be enhanced opportunities for what we do.”

Opportunities that prison companies helped create.

Produced by NPR’s Anne Hawke.

THE CASE OF IMAM JAMIL ABDULLAH AL-AMIN

A RUSH TO JUDGMENT?

THE COMMITTEE FOR TRUTH AND JUSTICE was organized in response to an abundance of misinformation and misleading information which has been generated by various law enforcement agencies and the press in the case of IMAM JAMIL ABDULLAH AL-AMIN and the shooting of two Fulton County Sheriff’s Deputies on March 16, 2000. We are a non-religious, independent coalition seeking to uncover and expose the truth and secure justice for all involved in this very disturbing case.

Is a Government Conspiracy Conceivable?

Yes. There is a long and documented history of government and law enforcement “counterintelligence” attacks on activists in the Black community. In the 1960’s, Imam Jamil (then known as H. “Rap” Brown) was first targeted as leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) to be “discredited” and “destroyed.” He has been subjected to surveillance, harassment and frame-up attempts in the years since his days as a student activist.

In 1995, the Atlanta Police Department arrested Imam Jamil on aggravated assault charges following the shooting of a 22-year-old man in the West End community. We have secured a notarized affidavit from the man who was shot testifying that the police attempted to threaten and coerce him into falsely identifying Imam Jamil as “the shooter.” The man refused to lie. The Atlanta Police Department’s attempt at witness intimidation was even reported in the mainstream press. After an outpouring of community support and charges of a “frame-up,” the prosecutor declined to go forward with the charge. However, heavy police surveillance of Imam Jamil and the Muslim community he leads has continued.

We believe that it is possible that the reason Imam Jamil and his community continue to be surveilled and harassed by the police is because of their well-documented—and highly praised—efforts to clean up the West End community of its’ drug and prostitution problem.

Based on Imam Jamil’s background and our knowledge of history, we most certainly consider “government conspiracy” to be a very real possibility—even probable. What do you think?

THE FACTS ON AL-AMIN

FACT 1 In 1999, Imam Jamil was stopped while driving by Cobb County Police. During the stop, the officers asked Imam Jamil for proof of insurance of the vehicle he was driving. He had a valid driver’s license but no insurance. According to the Imam, when he was to open his wallet, an officer spotted a metal badge. Imam Jamil informed the officer that the badge was issued to him by the city of White Hall, Alabama, when that city’s Mayor appointed him to the city’s auxiliary police force. At no time did Imam Jamil represent himself as an Atlanta police officer. (Source: essay of Prof. Natso Taylor Saito, Georgia State University Law School, 3/20/2000.)

FACT 2 During the stop, the Cobb County policeman made a check on the car the Imam was driving and their records listed the car as stolen. Imam Jamil provided the authorities with a bill of sale for the car, yet the police nevertheless arrested him for receiving stolen property. He was also charged with driving without insurance and impersonating an officer. (Soure: Prof. Saito, 3/20/2000.)

FACT 3 Imam Jamil missed a court appearance in January of this year, in connection with these small, non-violent charges. A bench warrant was issued for his arrest. On March 16, the day in which Muslims were celebrating one of their two holy days – ‘Id al’Adha’—two police officers came to a store which was owned by the Imam to serve the warrant.

FACT 4 There have been inconsistencies in the statement concerning how the shooting occurred. Some reports claim the officers were confronted with a man near a black Mercedes Benz, near the store. (Imam Jamil does not own such a car.) When they asked this man to show his hands, the man fired upon the officers. Another report states the man was inside the care and when asked to show his hands, the driver fired upon the police. (Sources—Prof. Saito, 3/20/2000; Atlanta Journal and Constitution: “Sheriff’s Deputies blind-sided by attack “ 3/18/2000).

FACT 5 The shooting occurred around 10 p.m. in an inner-city neighborhood. Initially, the surviving deputy could not identify his assailant but nonetheless a nationwide manhunt for Imam Jamil was announced. The following day, between medical operations, the deputy identified Imam Jamil from a photograph shown to him at the hospital. Despite these inconsistencies, the media reported that the surviving police officer “positively identified Imam Jamil.” (Sources—Prof. Saito, 3/30/2000; Atlanta Journal and Constitution: “Sheriff’s Deputies blind-sided by attack “ 3/18/2000).

FACT 6 Atlanta and Fulton County law enforcement wrongly told the media the initial warrant the police had sought to serve on Imam Jamil was for aggravated assault. They later admitted the information they put out was false. (Sources: Atlanta Journal and Constitution, 3/18/00; Hype Newswire: Media Rush to Judgment in the H. Rap Brown Al-Amin case, March 2000).

FACT 7 The Fulton County police reported that the “shooter” had been wounded and that they were following a trail of blood. However, medical officials have now verified that Imam Jamil is not wounded and thus the blood trail could not have come from him. Recently released Atlanta police records show a man was seen bleeding and begging for a ride five blocks from the shooting scene minutes after the shooting. Another recently released radio dispatch showed sheriff’s deputies searched for a wounded gunman and even surrounded the abandoned home where the blood was found. (Sources: Atlanta Journal and Constitution, “Police doubt bloodstains linked to Al-Amin case, 3/24/2000; “Al-Amin tape showed officers searched for wounded gunman.”

FACT 8 Imam Jamil stated the incident was part of a government conspiracy. This would not be the first. On August 7, 1995, Imam Jamil Al-Amin, while driving his son to school, was arrested in connection with the July shooting of a young man in Atlanta. After the arrest, the police interrogated his 7-year-old son for six hours before notifying someone to pick up the child. The victim initially pointed to Imam Jamil as his assailant. Later, in a news conference in Washington, D.C., this young man announced that he did not know who wounded him and that the police pressured him into making the identification. (Sources: Prof. Saito 3/20/2000; Washington Post, “60’s Militant Arrested in Alabama,” 3/21/2000; “Al-Amin calls slaying case a government conspiracy,” 3/22/2000).

FACT 9 The FBI and local law enforcement have continually made every effort to pollute the Atlanta jury pool and ensure Jamil Al-Amin could not receive a fair trial. Numerous reports had surfaced linking Al-Amin to crimes such as gun-running, domestic terrorism, up to 24 murders, as well as bank and armored car robberies in a concerted effort to remove all potential sympathy Imam Jamil may have had in the Black community. None of these allegations ever resulted in an arrest, nor was there sufficient evidence to do so. (Source: Atlanta Journal and Constitution” Eye on Al-Amin: police tracked militant inner circle in 90’s homicides,” 4/1/2000; and Atlanta Journal and Constitution “Al-Amin’s brother denounces frenzy” 4/4/2000.)

(Ed. note: Imam Jamil Al-Amin was convicted and is serving life in prison in Colorado.)

_________________________________________________________

Modern day debtors’ prisons devastating the poor

By Charlene Muhammad -National Correspondent- Final call

Last updated: Oct 15, 2010 – 3:17:38 PM

(FinalCall.com) – Poor men and women exit America’s prisons and jails, believing that they have paid their debts to society, but a new prison study by the ACLU revealed that many are being locked up or threatened because they cannot afford to pay their legal fines.

After a year-long investigation into the assessment and collection of fees associated with criminal sentences in Louisiana, Michigan, Ohio, Georgia, and Washington, the ACLU reported in “In for a Penny: The Rise of America’s New Debtors’ Prisons,” that courts across the U.S. were profiting from debtors’ prisons by violating a Supreme Court decision ordering courts to investigate a person’s inability to pay before returning them to prison.

“In some cases the courts are making decisions to incarcerate someone and the courts are not bearing the costs of having to incarcerate them, so they can make decisions based upon what they feel is appropriate in the circumstances of a defendant without having to bear the consequences of that decision,” said Attorney Eric Balaban, Senior Staff Counsel for the National Prison Project of the ACLU.

In New Orleans, for example, the court’s aggressiveness to collect fees stems from the important part those fees play in their operational budget but the money to pay Sheriffs to house men and women who cannot pay those debts are borne by the city, not the courts, he said. One Ohio town with a population of 60 collected more than $400,000 in one year of fees or officially, legal financial obligations, from the mayor’s court.

Two of the cases uncovered by the ACLU’s investigation were:

•A homeless construction worker in Louisiana named Sean Matthews was convicted of marijuana in 2007 and assessed $498 in fines and costs. After being arrested two years later for failure to pay the fines, he was sent to jail for five months, but it cost the City of New Orleans more than $3,000.

•Kawana Young, a single mother of two in Michigan, was arrested in March and spent three days in jail for failing to pay $300 in fees surrounding minor traffic offenses. Recently laid off and unable to find work, she incurred booking fees for her daily room and board.

According to Atty. Balaban, there are certain fines that undoubtedly disproportionately affect people of color. “African Americans make up 12 percent of the population. As of 2007 they made up approximately 38 percent of the incarcerated population and there are specific fines and fees that only people who are in prison and jail have to pay,” he said.

Those fees include fees for the booking and intake process, and so-called pay-to-stay fees for each day entities house an inmate. “Given that African Americans and people of color are disproportionately represented in our nations’ prisons and jails, those particular fines and fees disproportionately affect them,” Atty. Balaban said.

Although the ACLU sought statistics that indicated by race the number of men, women, and children who were incarcerated due to unpaid legal debts, none of the jurisdictions could provide the information, saying they did not keep those figures, especially by race, except Washington State, he said.

Washington State looked at the issue after the Washington State Supreme Court commissioned a study looking at racial disparities in the imposition of fines and fees for people who had been convicted of felonies. He said it found that Hispanics were likely to receive much higher fees than their White counterparts. People convicted of drug offenses were likely to receive higher fees than people convicted of violent offenses, and people of color were more likely to be searched, charged, arrested, criminally prosecuted, and convicted of drug offenses in Washington State and throughout the country than people who are Whit“But certainly, the courts have found this and it’s not surprising to say that racial disparities exist at every stage of the criminal justice process, not just in our prisons and jails,” said Atty. Balaban.

Atty. Balaban told The Final Call that the ACLU first learned of the problem in 2009 through Edwina Nowlin, who contacted them after she was jailed in Michigan for not paying court-ordered monthly lodging fees charged by the detention facility that was holding her juvenile son. She was homeless and working part-time at the time she was ordered to make the payments, Atty. Balaban said.

The ACLU in Michigan filed an emergency motion on her behalf and she was eventually released. After her release, the organization’s National Prison Project and Racial Justice Program conducted a survey to find out just how widespread her experience was.

Their survey focused on geographically diverse states, states that had larger urban populations than others where the problem seemed to be confined to more rural areas, and states where the problems they had heard about was emblematic of the problems across the country.

“We haven’t heard from Congress or received any feed back as of yet but we’re very hopeful that Congress will hold oversight hearings on this,” Atty. Balaban said. The ACLU has made specific recommendations to state and local officials to ensure that: defendants are not incarcerated because they cannot pay fines and fees that they can’t afford and that courts consider their ability to pay when deciding whether to assess more fees.

The study further recommended that states should repeal all laws that may result in poor defendants being punished more severely than defendants charged with the same offenses who have means.

Geri Silva, executive director of Families to Amend California’s Three Strikes Law, said the back story is that constitutionally, everybody is guaranteed a right to counsel, whether they can pay or not, so it is clear from the beginning that people are not going to be able to pay.

She said the irony is that states are jailing people in “cash-strapped” cities for failing to pay their legal fines, but turn around and pay triple or quadruple that amount to put people in jail. “It sort of leads one to believe that perhaps jails and prisons are money making enterprises for the states. All roads lead to prison and all thinking leads to the fact that if they’re filling these prisons, it’s not about public safety obviously but it has to have something to do with financial gain for the industry itself,” Ms. Silva said.

She reiterated “In For a Penny’s” position that men and women who are re-entering into society from prison already face tough obstacles. They have to try to rebuild their lives with reduced or no incomes, worsening credit ratings, poor housing prospects, and greater chances of recidivism.

“How far will they go? Who are they trying to kid with this? How do you get blood out of a turnip? How does somebody who can’t pay, pay? Will they then find the one person who had their nails done or something instead of paying? Is that what they’re going to do to justify this insanity,” Ms. Silva asked.

According to Ms. Silva, all of these issues that hang over a poor person who has been incarcerated stem from America’s building an industry that is skewed, sinister, uncivilized, and centered on punishment. Ask taxpayers if they would rather pay $600 in legal fees or thousands in jail costs and they would pick the more sensible route of less costs, she said.

“The industry itself is tremendous. Can you imagine what it takes to run, say, California State Prisons in terms of food services, clothing, armaments, initially the building trades? It’s a multi-billion dollar industry that a great number of people are getting fat off of so it’s so disingenuous for them to say they’re losing money because people aren’t paying their fees,” Ms. Silva added.

Critical Resistance is a prison advocacy group based in Oakland, California that works with people who are incarcerated and re-entering society. Isaac Ontiveros, communications director, said that the ACLU’s report unveiled yet another example of the way that the Prison Industrial Complex works to imprison and police people, and how it creates, exacerbates, and thrives on debt and creating debt traps.

People spend a number of years in prisons or jails and the first thing they come out to is an enormous pile of debt, and that affects their inability to gain access to resources around re-entry support, Mr. Ontiveros told The Final Call.

“We’re talking basic things like transportation vouchers, housing, job opportunities, they end up being left with a pile of debt and we see how that debt just lands them back in a cage … The thing to look at is who’s being policed, imprisoned, thrown in jail around these tiny infractions and if we look at what communities people are coming out of I don’t have to guess that it is poor people, people of color, and that the state, local government puts a premium on policing people of color,” he added.

He said the whole idea is around social control and who is desirable and who is not. One solution is to prioritize resources to create programs that build up communities. The pressure for those resources will come from the ground, grassroots mobilizing, not from politicians on local, state, or national levels.

“It’s going to come from people from the community, organizing their community, and either building these things themselves, or putting pressure on politicians to make a demand for resources to be used for things that have shown time and time again to build up communities,” he added.

According to Kurt Kaaekuahiwi, an intern with Critical Resistance, the definite intent of debtors’ prisons is to keep people within the system, but resources should be put into educational or job training programs within prisons to help those men and women re-entering secure jobs once they are released.

“We have to divest from policing, divest from incarceration, and divest from prison expansion. Obviously, these monies that are being appropriated are through the general fund, which is from our tax dollars, and being used to further criminalize, stigmatize, and keep us trapped in the system, but that money is not used to support our needs of affordable housing or job opportunities,” he said.

(The full report: “In for a Penny: The Rise of America’s New Debtors’ Prisons,” can be read at www.aclu.org/prisoners-rights-racial-justice/penny-rise-americas-new-debtors-prisons)

Related news:

America’s New Slavery: Black Men in Prison (FCN, 03-20-2008)

Follow the Prison Money Trail ..to elected officials (In These Times, 09-04-2006)

SEE LINK TO FINAL CALL AT RIGHT OF THIS SITE.

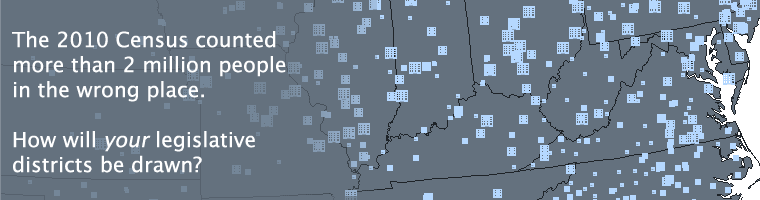

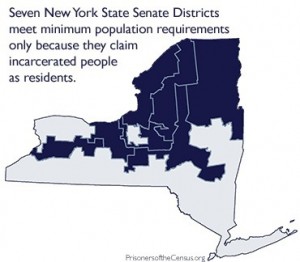

NEW YORK COUNTS PRISONERS IN HOME DISTRICTS

NEW YORK COUNTS PRISONERS IN HOME DISTRICTSBy Dr. Publico–American Tribune

“Gov. David Paterson of New York took a stand for electoral fairness earlier this month when he signed legislation that bans prison-based gerrymandering — the cynical practice of counting prison inmates as “residents,” to pad the size of legislative districts. The new law, which requires that prison inmates be counted at their homes, deserves to be emulated all across the country.” New York Times editorial, 8/22/10

Some years back, I received a notice from the prison mailroom that a letter containing an application form for an absentee ballot was rejected by the prison and sent back. On the notice, the mailroom guard had written, “When you were sent to prison, you lost your right to vote!”

Going to the mailroom, I told the supervisor that there was no such law. States determine specific voting laws and they’re all different. Prisoners from some states can vote. The letter had been part of my procedure for checking on the status of my own state.

He snapped that it was federal law, and that I was a federal prisoner. When I asked what law he was talking about, he glared at me and asked, “Who do you plan on voting for?”

When I didn’t answer, he said, “I thought so. Well, you can’t vote. And if you don’t get outta my face right now, I’m gonna kick your fuckin’ teeth down your throat!”

In the final analysis, that’s what prison is all about: Ignorance and the rule of raw power.

Part of the ruling regimen of retribution and punishment includes “civil death”: the loss of all civil rights. In old Europe, the term “outlaw” was associated with individuals guilty of treason (by their lordly masters) or convicted felons. It was carried over into colonial and American law.